TL;DR: A client’s legacy SilverStripe site was 500ing on every admin workflow that mattered. The job was simple: build a bot to extract the data and send reports to my client. I did that by lunch. Then my brain goblin wouldn’t let it go. I haven’t written PHP since the dark ages, but I got FTP access, built a CLI toolbox to give my AI agent eyes and legs, and let it track down the bugs semi-autonomously. Deployed fixes file-by-file over FTP. In 2026. A beautiful disaster.

A Confession

I’ll be honest: I have a thing for dirty code.

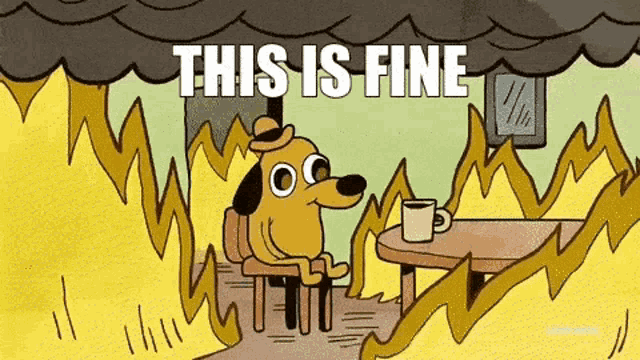

Not my dirty code - I write pristine, well-architected systems that definitely don’t have // TODO: fix this later comments from 2019. No, I mean other people’s dirty code. Legacy systems. The kind of codebase where the README says “just works” and the reality says “just barely.” Hand me FTP credentials to a decade-old PHP site that’s held together by session variables and sheer institutional denial, and something in my brain lights up like a Christmas tree.

Most developers see a legacy dumpster fire and feel dread. I feel the same thing a cave diver feels staring into a dark hole in the ground: this is going to be awful, I might not come back the same person, and I absolutely cannot wait to go in.

So when a client’s legacy SilverStripe site landed on my desk - “not working,” they said, which undersells it the way “the Titanic had a minor hull issue” undersells maritime history - I didn’t groan. I cracked my knuckles.

Key admin workflows - filtering orders, exporting CSVs, pulling statistics - all produced HTTP 500s. The people who needed this data couldn’t get it. The site was a locked filing cabinet that electrocuted you when you touched the handle.

The existing workaround was… creative. Since the export was broken, someone had set up an AI agent to intercept every outgoing customer PDF - invoices, receipts, confirmations - and scrape the numbers out of them to reconstruct the data the admin panel couldn’t provide. An AI reading every piece of customer correspondence to reverse-engineer the database. In production. With real customer data.

I’ll spare you my exact reaction. What I said was “I’ll take a look at the site.”

The ask was straightforward: build a bot that extracts the data the admin panel can’t export, and send the reports to my client. That’s it. No fixing the site. No debugging. Just get the data out.

All I had to work with was my client’s admin login credentials and the live web UI. No server access. No FTP. No SSH. No deployment pipeline. Just a username, a password, and a website that 500’d if you looked at it funny.

The plan was simple: build the bot, get the data flowing, hand it over, walk away. A clean, scoped engagement. In and out. No long-term commitment.

You can probably guess how that went.

Phase 1: Build the Bot (The Actual Job)

First order of business: the client needed order exports today, and the export button was one of the things producing 500s. So I needed a workaround that bypassed the broken UI entirely.

I wrote a Python exporter that logs into the admin panel - using my client’s credentials - and triggers the same SilverStripe GridField export actions a human would click, except it does it over HTTP, with structured logging, and without crashing. Added redaction to the HTTP logs so cookies and CSRF tokens wouldn’t end up in version control, because I’ve read enough post-mortems to know that’s how you get a second incident.

Even while the building was on fire, I refactored the exporter into a clean src/ layout with shared modules, consolidated the helper code, and ran python -m compileall as a sanity check. Professionalism is a disease - you can’t turn it off even when you should.

By mid-afternoon, non-technical team members could trigger exports through a chat slash command and get the CSV back in their messaging client. No admin panel required. No 500s. Just data. Oh, and the AI agent that had been reading customer PDFs to reconstruct export data? Quietly retired.

I also wrapped the exporter in a serverless function for a more ops-friendly hosting option, and added CI that automatically exports the past month’s data on every push and uploads it as an artifact.

Job done. Bot built. Data flowing. Walk away.

I did not walk away.

The Brain Goblin

The bot worked. The reports were landing. My boss was happy. The rational thing was to close the laptop and move on.

But the site was still broken. The admin panel was still 500ing. The filters were still lying. And somewhere in the back of my skull, a small, irresponsible voice was saying: you could fix this. You know you could fix this. It would be so satisfying to fix this.

I call this voice the brain goblin. It’s the part of my brain that sees a dumpster fire and doesn’t think “someone should deal with that” - it thinks “I should deal with that, right now, tonight.”

There’s a catch, though: I’m not a PHP developer. I was, once, in the dark ages - back when mysql_real_escape_string was considered security and deploying meant dragging files into FileZilla. But that was a long time ago. I couldn’t fix this myself. But I could build the tools to let an AI agent fix it for me.

Here’s the thing about AI agents and legacy PHP: the agent is a better PHP developer than I am. It can read SilverStripe framework code, trace ORM call chains, spot N+1 patterns, and suggest fixes in a language I haven’t seriously written since the Bush administration. What it can’t do is see what’s happening on a remote server. It can’t read logs that live behind FTP. It can’t query a database it doesn’t have credentials for. It can’t upload a patched file.

The agent was a brilliant surgeon. I needed to build the operating room.

I got FTP access. And from there, the plan took shape: build CLI tools that let the agent - and me, when I’m feeling brave - fetch evidence over FTP. Tail logs. Query the database. Upload surgical fixes one file at a time. Every tool I built was a new sense organ for the agent. FTP log tailing gave it eyes. The database CLI gave it memory. The file-by-file deploy script gave it hands. Without the toolbox, the agent was a brain in a jar. My job was to build the jar some legs.

This all kicked off on February 3rd. Most of it was done by midnight. I have the commit history to prove it, and the commit messages to prove I was losing it.

Phase 2: Build the Toolbox (So the Agent Can See the Fire)

The constraints were, as they say, chef’s kiss. FTP/FTPS access. No SSH. No deployment pipeline. Changes had to be uploaded file-by-file, like it was 2003 and we were all pretending this was fine. Some requests died before SilverStripe could even log them - Apache would just emit “End of script output before headers,” the server equivalent of a shrug, and move on. I was debugging a crime scene where the victim, the witness, and the detective were all unconscious.

But the FTP folders had secrets. MySQL credentials in a config file - that got me database access. And like any good lock, it had more doors behind it. FTP alone was painfully slow for exploratory debugging. I needed something closer to shell access - the ability to poke around the filesystem, check PHP config, look at things FTP couldn’t show me. So I did what any principled engineer would do: I uploaded a web shell.

My own, temporary, purpose-built. Just enough to get SSH-like visibility when all I had was HTTP and FTP. I used it to dig around, gather intel, understand the server environment - and then removed it once I had what I needed. Is this the kind of thing you put on a resume? No. Is it the kind of thing you do at 11 PM when the building is on fire and the only door they gave you is FTP? Also yes.

So I built a portable CLI toolkit, piece by piece - each tool designed to give the AI agent one more sense:

FTP log tailing. A script that connects over FTPS, downloads the latest log entries, and formats them locally. The agent could now read error logs without me manually copying them. Because tail -f is great when you have SSH. When you have FTP, you improvise.

Read-only database CLI. A command-line tool that talks to the remote database, with guardrails - only SELECT, SHOW, DESCRIBE, and EXPLAIN are allowed, and it rejects multi-statement queries. I needed the agent to inspect data, not accidentally DROP TABLE a client’s order history because of a fat-fingered semicolon. Yes, I wrote unit tests for the query guardrails. In the same week as the production firefighting. Like I said: disease.

FTP put for file-by-file deploys. Upload exactly one changed file and nothing else. Verify by re-downloading the remote file and comparing SHA256 hashes - or git diff --no-index for the paranoid (me). This became the deployment “pipeline.” It’s the saddest CI/CD you’ve ever seen, and it worked perfectly.

This was the turning point. The repo stopped being “just an exporter” and became a portable operations toolbox - the agent’s nervous system for a site we could only reach by FTP.

Phase 3: Bring the Site Into Version Control (So You Can Think About It)

You can’t reason about code that exists only on a remote server you access via FTP. So I mirrored the entire webroot locally and committed it. A download script using eight parallel FTP connections pulled 1,302 source files - PHP, JS, CSS, templates, configs - with zero failures. For the first time in this site’s life, it was in version control.

I told the agent explicitly: source files only. No media. Do not download images.

It downloaded 300 GB of media before my SSD ran out of space.

I only noticed because JetBrains Rider popped up a low disk space warning. The agent had decided, with the quiet confidence of a golden retriever carrying a tree branch through a doorway, that “mirror the webroot” meant mirror the webroot. Every customer photo. Every generated thumbnail. Every asset uploaded since the mid-2010s. And 300 GB wasn’t even the full haul - the server’s 3 TB drive had 1.8 TB used. My SSD just tapped out first. We had a conversation about boundaries.

Let me paint you a picture of absolute chaos.

The webroot wasn’t just one website. It was every website. Side by side. The server had accumulated what I can only describe as a geological record of deployment strategies: website_v1, website_v2, website_v3, website_old, website_really_old - all sitting right next to the actual production folder. Nobody had cleaned up after a migration. They just… started a new folder and left the old one there. Version control by directory naming. A relic of a time before Git, before deployment pipelines, before anyone thought “maybe we shouldn’t keep every version of the site on the production server forever.”

Customer-generated images were scattered across folders with no discernible organizational logic - or just dumped directly in the webroot. Thousands of images in the root folder. I didn’t know a web server could sustain that level of neglect and still serve pages. And nestled among the chaos: a zip export from literally ten years ago. “Should have been deleted a few days after generation,” they told me later. Ten years.

The server wasn’t just unmaintained - it was a digital attic where nobody had ever thrown anything away. Every past decision, every abandoned migration, every “temporary” file from the mid-2010s, all coexisting peacefully with production like roommates who’ve stopped acknowledging each other.

I also started writing structured bug reports - symptoms, evidence, hypotheses - as separate markdown files, because by this point I had enough threads going that my brain alone was not a reliable storage medium. The error log became a cemetery. I tagged each grave.

Speaking of error logs: I pulled roughly a year’s worth - February 2025 through February 2026. 2,024 logged error events. Promising. Then I noticed 1,928 of them were the same bug on a profile endpoint, screaming on repeat like a car alarm nobody disconnects. Ninety-five percent of the error log was one bug drowning out every other signal. The actual admin 500s I was hunting? Barely a whisper underneath.

From here, we could treat fixes like normal engineering: the agent traces the issue through the codebase, suggests a patch, I review it, commit, upload the changed file, verify by re-downloading and diffing.

It felt like putting on glasses after years of squinting. Same site. Suddenly legible.

What Was Actually Broken

Here’s where it gets fun. “Fun.”

Bug 1: The Type Filter That Referenced a Ghost Column

The admin orders page had a “Type” dropdown filter. When you selected an option, the UI sent a query parameter like q[Type]=CouponItemID. The server-side code obediently tried to filter on a column called CouponItemID.

That column didn’t exist.

The dropdown values were raw internal identifiers that some past developer had wired directly into the UI - and at some point the schema had changed underneath them. The filter was sending SQL WHERE clauses into the void, and the database was responding the only way it knew how: by dying.

The fix: change the dropdown values to semantic keys and map them to the columns that actually exist in the filter logic. Fifteen minutes of work, once you know where to look. Finding where to look took considerably longer.

Bug 2: The Filters That Didn’t Filter (And the Export That Paid the Price)

This was the big one. Not one bug, but a constellation of failures that all pointed in the same direction: the database was always loading everything.

Most of the admin filters were broken. They looked functional - dropdowns selected, date ranges set, UI updated - but under the hood, the filter state wasn’t being applied to the actual query. Every admin page load was hitting the unfiltered dataset. The only thing standing between the user and a full table scan of 19,500+ orders was pagination. The paginator sliced the results to 50 rows for display, and that kept the page technically loading.

But even the paginated view was lying. In the background, result.count() was still counting the entire unfiltered dataset - every time. The UI would show “1–50 of 19,550” regardless of what you’d filtered to, because the count didn’t know about the filter either.

Then someone clicked “Export as CSV.”

The SilverStripe GridField export action does something reasonable in theory and catastrophic in practice: it removes pagination. All of it. It tries to export the entire result set in one go. When the filters work, that’s fine - you’re exporting a bounded dataset. When the filters are broken and “the entire result set” means every order the company has ever taken, combined with summary fields that traverse ORM relationships per row - classic N+1 - you get a request that churns for about 25 seconds, then either times out, exhausts PHP’s memory, or crashes the process before headers are even sent. Apache would return a raw error page with almost no SilverStripe headers. PHP was dying in the hallway before it could reach the error handler.

The fix came in three layers:

Mitigation: If an export request came in without explicit date filters, default to a bounded date range. Stop trying to export the entire history of the company in one HTTP request.

Correctness: Make the export action URL carry the current filter state, so the export respects whatever the admin actually filtered to. This required changes in both the framework’s JavaScript (GridField.js) and the server-side code - the export button was ignoring filters entirely.

Performance: Override the export columns to avoid expensive per-row relationship computations during large exports. You don’t need to traverse three levels of ORM relations to produce a CSV.

Bug 3: Date Filters That Filtered on the Wrong Date

The admin date presets - “Last 7 days,” “Last 3 months,” “Today” - were filtering on the wrong timestamp column. The paginator count didn’t reflect the filtered list. Filter state wasn’t persisted across page loads.

That last one had a framework-specific root cause that took a while to find: in SilverStripe’s GridField, data manipulators apply in component order. My date filter manipulator was running after the paginator, so the paginator computed its totals against the unfiltered list. The UI would claim “1–50 of 19,550” even when you’d selected “Last 3 months.” Later pages were empty.

Multiple fixes over a few hours: correct the timestamp column, fix the preset logic, insert the date filter component before the paginator, and add session-backed persistence. A follow-up the next day set a sane default (“Past 3 months” instead of “everything ever”) and highlighted the active preset in the UI.

Small bugs, individually. Collectively, they made the admin panel feel like it was gaslighting you.

Bug 4: “We Can’t See the Error”

The meta-bug. The reason everything else took so long.

Some failures happened entirely in PHP’s shutdown phase - fatal errors, uncaught exceptions, memory exhaustion. SilverStripe’s error handler never ran. Apache logged a one-liner. The admin saw a blank page or a generic 500. Nobody knew what broke.

I added temporary, gated observability: log fatal shutdown errors and uncaught exceptions to a writable temp file (readable over FTP), and optionally stream detailed error output to the response - but only for authenticated admins, and gated behind a flag that defaults to off. Just enough visibility to diagnose, without turning production into a confessional booth for every visitor.

This was the “we can’t fix what we can’t see” part of the story. Once I could see - or rather, once the agent could see, through the tools I’d built - every other fix fell into place within hours.

Bug 5: The Statistics Page That Rendered the Entire Universe

This one wasn’t a 500 - it was a 200 that took minutes.

The statistics admin page rendered all tabs server-side in a single initial request. Orders, coupons, registrations - everything, all at once. That’s why clicking between tabs felt instant afterwards: there were no additional HTTP requests. The page had already done all the work upfront, like a waiter who brings every item on the menu to your table and asks you to pick.

Under the hood, the compiled templates called Count(), sum(), and column() helpers repeatedly - each one typically firing SQL. But the real horror was a filter stats code path that iterated roughly 14,000 records and executed a COUNT(*) per record. N+1, at scale. The underlying table had approximately 6.7 million rows with no indexes besides the primary key. A single text-matching filter query (LIKE '%something%') against that table took about 13 seconds. Multiply by 20 filters and you’re looking at minutes of wall time for one page load.

The fixes: rewrite aggregate queries to avoid N+1 loops, cache repeated group/member lookups per request, apply a default date range on entry so the page doesn’t try to summarize all of recorded history, and optimize relationship-based queries to stop building enormous IN (...) lists. Performance went from “go make coffee” to “tolerable.” Still not fast. But the building was no longer on fire, and I’d promised myself a clean break.

The Server Punches Back

One more thing. After deploying a fix, I got an immediate Parse error: unexpected '?' in production.

The fix used PHP’s ?? null coalescing operator. The server’s PHP version was too old to support it.

I rewrote it as isset($x) ? $x : $default, re-uploaded over FTP, and added “the server is running ancient PHP” to my mental model. The building wasn’t just on fire - it was built from highly flammable materials.

Oh, and sometimes I’d upload the correct fix and the site would still show the old behavior. OPcache had decided the previous code was fine, actually, and combined JS caches weren’t helping either. The mitigation was a combination of ?flush=all, clearing the combined-files cache directory, and occasionally toggling settings in the hosting panel to nuke the opcode cache. You haven’t lived until you’ve debugged a fix that’s correct but invisible because the runtime is nostalgic.

Aftermath: Turn the Chaos Into Repeatable Operations

Once the fires were out, I turned the one-off tooling into something reusable: user export CLI with registration filters, integration with an email marketing platform as a serverless function, and - critically - documentation. Split and structured so that the next person who gets handed FTP creds and a vague description of “it’s not working” has a slightly less terrible day than I did.

A couple weeks later, another production issue surfaced: path handling bugs where $_SERVER["DOCUMENT_ROOT"] resolved to /framework under SilverStripe routing instead of the actual webroot. Replaced brittle document root references with Director::baseFolder() and hardened the CLI image generation scripts to normalize paths properly. Same workflow - patch, commit, FTP upload, verify. The toolbox held up.

Oh, and they gave me SSH access. After I’d already fixed everything. Classic.

The Vibe Check

Deployment Sophistication Meter: [██░░░░░░░░] 2/10

✅ Changes are in version control

✅ Diffs are verified post-deploy

✅ Database access is read-only by default

✅ Exports work without the admin panel

✅ Unit tests exist for the FTP and DB tooling

✅ AI agent can autonomously trace bugs through the codebase

❌ "Deployment" means FTP put

❌ "Rollback" means FTP put again, but the old file

❌ "Monitoring" means running a script that tails a log over FTPS

❌ The server's PHP version doesn't support ??

❌ SSH arrived after the war was over

❌ It's 2026

FAQ (Mostly Honest)

Why didn’t you just set up SSH? They gave me SSH. After I’d already fixed everything. You work with the door they give you, even if that door is FTP, and even if they install a better door the day after you’re done.

You uploaded a web shell to production? A temporary one. For diagnostic purposes. Removed afterwards. Look, when your only access is FTP and you need to understand the server environment now, you do what the situation demands.

Isn’t this just a glorified set of curl scripts? Yes. But glorified curl scripts with guardrails, unit tests, structured logging, and documentation. That’s the difference between a hack and a tool.

Why Python for the exporter? Because it needed to exist in an hour, not be beautiful. Python is the language you write when the building is on fire and aesthetics are a luxury.

You wrote unit tests during a production firefight? Yes. For the FTP helpers and the DB read-only guardrails. In the same week I was uploading PHP files one at a time over FTPS. Professionalism doesn’t have an off switch.

How much did the AI agent actually do? More than me, honestly. I built the toolbox - the FTP scripts, the DB CLI, the deploy workflow. The agent did the actual PHP archaeology: tracing SilverStripe framework code, identifying the broken filters, spotting the N+1 patterns, writing the patches. I’m not a PHP developer anymore; the agent is. I just gave it eyes and legs and pointed it at the fire. Though I did have to stop it from downloading 300 GB of customer photos onto my SSD, so the supervision wasn’t optional.

Why didn’t you just stop at the bot? Because the brain goblin doesn’t negotiate. The bot was the job. Everything after was compulsion dressed up as initiative.

Will you ever stop being dramatic about FTP? No. It’s 2026 and I deployed production fixes by uploading PHP files one at a time. If anything, I’m under-dramatic.

Do you actually enjoy this kind of work? I know what I said. Don’t judge me.

What I Actually Learned

The technical fixes were straightforward once you could see them. The hard part was building the scaffolding to see them in the first place. Every hour I spent on tooling - the exporter, the log tailer, the DB CLI, the FTP deploy workflow - paid for itself ten times over in the hours that followed.

There’s a lesson here about AI agents, too. An agent with a powerful language model and deep framework knowledge is useless if it can’t see the system it’s debugging. It can reason about code, but it can’t read a log file on a remote server. It can suggest a fix, but it can’t upload it over FTP. The bottleneck was never intelligence - it was access. Building the toolbox wasn’t just helping me work faster. It was giving the agent a body.

When someone hands you a broken production system and a set of constraints that feel impossible, the instinct is to start fixing things immediately. The better move is to spend the first few hours making the system legible. Mirror the code. Write down what you see. Build tools that let you look without touching.

Then the fixes find themselves.

The site’s working now. The exports run. The filters filter. The admins can do their jobs without a 500 greeting them at every turn. I wrapped it up, documented it, handed it back, and walked away.

A clean break. Just like I promised.

But I’d be lying if I said I didn’t enjoy it. There’s something deeply satisfying about building an AI agent a nervous system out of FTP scripts and Python guardrails, pointing it at a decade-old dumpster fire, and watching it methodically extinguish every flame - while you sit there reviewing patches in a language you haven’t written since the dark ages.

And yes, I deployed production fixes over FTP in 2026. The server’s PHP was so old my syntax was too modern for it. SSH arrived the next week. I regret nothing.